Extreme kayakers tackle Adirondacks’ wildest water

By Alan Wechsler

For more than a century, the narrow canyon known as High Falls Gorge has attracted thousands of tourists every year. From a catwalk and staircase bolted to the rock wall, visitors gaze into the dizzying rush of the West Branch of the Ausable River far below.

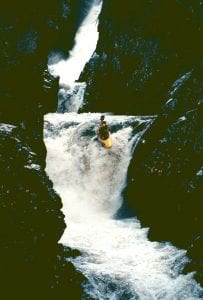

But one day last September, after the busy season, only a few tourists were on hand to witness an equally impressive sight—the first kayak descent of what could be the hardest river ever run in New York.

It’s also one of the most dangerous. At High Falls, the river drops more than 100 feet in a series of steps, shooting between slots in the black rock no more than four feet wide. There are hidden boulders and eddies with powerful back currents, dozens of places where even the world’s best kayakers can get into serious trouble.

“The matter of a boat being two inches off to the left is the potential between a successful run or being seriously hurt or killed,” says Mike Duggan, who has scouted the gorge for years.

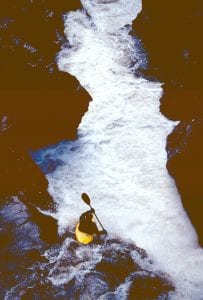

There’s a new standard of whitewater in the Adirondacks, and it’s not the Moose River or Hudson Gorge. Instead, the envelope is being pushed by a daring few in tiny, brightly colored plastic boats, paddling themselves down small rivers and streams and defying gravity in ways that ordinary folks might think suicidal.

Thanks to new plastics and innovations in boat construction, paddlers with great skill and the co-jones to match are turning the Adirondacks into a prime destination for extreme kayakers. Even now, kayakers say there’s more first-descent potential left in the Adirondacks than in any other place in the Lower 48.

And the small world of extreme kayaking is starting to pay attention. Last fall, American Whitewater magazine ran a cover story on the region, listing 65 different rivers to run: from the relatively placid North River stretch of the Hudson to Sluice Falls on the Middle Branch of the Oswegatchie, described as alternating “between long flat sections and hideous waterfalls, slides and chasms.”

The first attempt to run High Falls Gorge was made by Shannon Carroll, a professional kayaker from North Carolina. She got through one drop of about 20 feet, and her boat jammed in a crack. Using rescue ropes, a team of kayakers on the rim rappelled down and pulled her out of danger.

Four days later, Carroll and three other kayakers tried it again. First was Leland Davis, also of North Carolina. He made it halfway down, where he got stuck in a hydraulic—a boiling pool of water at the bottom of a waterfall that can trap a boat and pull it under. Someone threw Davis a rope from the catwalk, and he was pulled out of the hole to finish the run.

Next was Willie Kern of Stowe, Vt. He made it halfway down before his boat struck a rock. The sudden impact threw his body forward, smashing his face into the boat hard enough to leave tooth impressions on the plastic. He finished the run with blood pouring from his nose.

The third kayaker made it through OK. Then came Carroll, who didn’t even make it as far as the first day. Instead, she disappeared behind a waterfall and didn’t come out. “We didn’t see her for four or five minutes,’’ recalls Duggan, of Lake Placid. “We thought she was dead.”

Actually, Carroll was stuck in an air pocket behind the waterfall, but she could not be seen from above. It took nearly a dozen people with all their rescue ropes to pull her free. “You don’t have to worry about me doing it again,” she told High Falls Gorge owner Greg Silver.

Despite the risks, Duggan is considering giving the falls a go next season. A 38-year-old ski-store manager, he and a half-dozen of his friends have spent the last few years pushing the definition what is a runable river—and they’re not done yet.

“It’s pretty insane. Some of the things they run are incredible,” said Andy Teig, 29, of Lake Placid, a fellow kayaker. Duggan takes credit for being the first to kayak over Rainbow Falls and Twin Falls on the South Branch of the Grass (stretches of river that the state purchased just two years ago), Split Rock Falls and Shoebox Falls on the Boquet, the Flume on the West Branch of the Ausable, and Johns Brook in the High Peaks.

The crew got help from the weather last summer. The rain that ruined so many camping trips was a godsend to kayakers. It kept the rivers running high and fast all summer, similar to spring conditions but without the frigid waters. It was the equivalent of a ski resort getting four months of constant Champagne powder.

Many of the descents involve cascades up to 100 feet long and scraping slides down 45-degree slabs. Such trips are attempted only after the falls have been scouted and analyzed. And people are always standing by on shore with rescue ropes.

Even the experts get hurt. Duggan still has scars on his left wrist from raking his flesh over the sharp rocks at the Great Falls of the Black River near Watertown. And he almost knocked himself out once, hitting his head on a rock while heading down the Moose River backwards. He had run the Moose 200 times already, but this time he was yelling to a friend on shore and not paying attention, and he got turned around. “It was all my fault,” he says. “Total pilot error. It taught me a big lesson.”

There are greater dangers than a headache or mangled flesh. If you hit the bottom of a dropoff wrong, you can compress or break your spine. Come out of a waterfall facing the wrong direction, and you can get sucked into a hydraulic that can hold boat and paddler under until he drowns—life vest or no life vest. In fact, one of the pioneering Adirondack kayakers, Chuck Kern of Stowe, Vt. (Willie’s brother), drowned while running the Black Canyon on the Gunnison River in Wyoming several years ago.

Duggan has been running rivers for more than 15 years. He’s sponsored by Perception Kayaks, a boat manufacturer, and he owns half a dozen boats. His kayak is known as a “creek boat,” far removed from the heavy fiberglass kayaks used by whitewater paddlers of a previous generation. Creek boats are short, with a banana-shaped hull that allows it to turn on a dime and punch through large waves.

The new boats, made of high-impact plastic, weigh only about 35 pounds. They are built so kayakers can deliberately smash into rocks, a useful technique to escape backward into an eddy for a quick rest between falls. The boat’s interior is filled with foam padding that envelops the legs, so the boat becomes an extension of the paddler’s lower body.

On a typical outing, besides the $1,000 kayak, paddlers bring along a sprayskirt, a drytop jacket with sealed neck and wrist gaskets, a rescue vest made to hold a paddler’s weight if he or she needs to be hauled out by rope, elbow pads, a whitewater helmet, neoprene gloves and warm fleece underneath the jacket. A first-aid kit and a rescue rope in a throw bag completes the ensemble.

All that gear can weigh a lot, as Duggan and friends found out when they hiked three miles into the woods to make a first-descent of John’s Brook. The river is only runnable during high water, and even then it is chocked with car-size boulders. But it offers some of the most consistent and challenging whitewater in the mountains.

It’s also a long hike upstream. As many High Peaks hikers know, the brook flows out of the mountains not far from Mount Marcy, paralleling a foot trail for the last few miles before reaching the hamlet of Keene Valley. On several trips, Duggan and his colleagues each carried the 35-pound boats and 40 pounds of gear three miles up the trail to the ranger station, where they put in and set off downstream. On the way, they usually pass more than one startled hiker. “I’ve had people say, ‘I didn’t know there was a river out there,’’’ Duggan said.

After a big rainstorm, kayakers often have less than half a day to take advantage of the high water. While spring and fall are the best times to go, some die-hards have been known to take daring runs during a midwinter thaw. Duggan and friends once earned a first descent of the South Branch of the Boquet River in mid-January. The river was teeming with chunks of ice, and an emergency exit from the river would have been impossible—there were five-foot walls of ice lining the banks.

At times like this, it’s important to remember that this is supposed to be fun.

“It was a pretty neat change, a unique experience,” Duggan says, adding: “If you had gone swimming that day, you would have died.”

Ed Huber, 30, a videographer from Lake Placid, thinks there’s enough interest in kayaking in the Adirondacks to devote his full-time business to a company called Split Rock Video (www.splitrockvideo.com). It’s named after Split Rock Falls on the Boquet River, a popular swimming area off Route 9 near Elizabethtown—and another tricky run. Huber hopes to make a living photographing well-to-do kayakers on their descents.

Another friend, Dennis Squire of Albany, is working on a kayaking guidebook for the region. But the book may be premature. Duggan says there are still dozens of unrun streams and stretches of rivers in the mountains. Most are remote. Whether or not these rivers ever get kayaked depends on how willing people are to lug their boats for miles through the woods, sometimes bushwhacking the whole way. Other streams are so choked with brush that passage is all but impossible.

“Every drop has its own risks, moves that need to be made, rescue concerns, safety issues,’’ Duggan says. “There’s a lot of calculation and knowledge and experience. It’s not a kamikaze approach.”

Take that autumn day at High Falls Gorge. Duggan had every right to make the first attempt, considering how long he had studied the waters, figuring where to dip a paddle, where to bounce off a rock, where to aim the boat at the crest of a fall. But he didn’t feel right about it and opted out. In such cases, they say, it’s best to trust your instincts. The river, after all, will be there when you’re ready for it.

So you needn’t remind Mike Duggan that kayaking the gorge is a dangerous business. Yet he thinks the risk, when he’s ready, will be worth taking. “After running something like that, I feel more alive than any other time,” he said.

Leave a Reply