By Rick Karlin

This is how it was meant to be. The wax is holding firm as we ascend the mild uphill behind Pitchoff Mountain and settle into a comfortable kick and glide through the still woods, slow enough to maintain conversation but fast enough to know we’re getting somewhere.

I’m skiing the Jackrabbit Trail with Tony Goodwin, who maintains, promotes and practically lives on the trail in winter. Goodwin was among those who thought up the Jackrabbit back in the mid-1980s. It was conceived as a European-style trail that would connect several communities, so people could ski from end to end over a few days, spending the night in town and dining in restaurants.

“Our thought was that if we built a trail the guide services would fall all over themselves to set up inn-to-inn ski trips,” says Goodwin, executive director of the Adirondack Ski Touring Council.

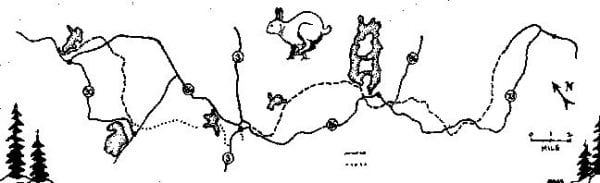

Alas, it hasn’t worked out that way. Although hundreds of people flock to the Jackrabbit each winter, most take short day trips. In a typical year, only a dozen or so parties make the 24-mile trek between Keene and Saranac Lake. Eventually, the ski council hopes to extend the trail to Tupper Lake to the west and to Paul Smiths to the northwest.

I intend to ski the Jackrabbit the way it was meant to be skied. On the first day, I’ll go from the Rock and River Lodge in Keene, the southern terminus, to Lake Placid and spend the night at Howard Johnson’s, which practically sits on the trail. On the second day, I’ll finish in Saranac Lake. That’s the plan, anyway.

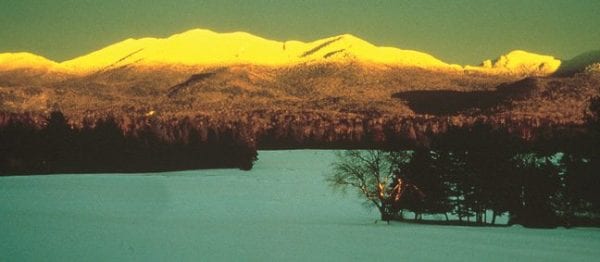

The Jackrabbit offers a wide range of terrain, scenery and challenges. On the same day, you may find yourself breaking trail in the “forever wild” Forest Preserve, gliding along a groomed trail at a commercial ski center or taking in the view of Whiteface Mountain from a golf course. Most of the hills are fairly gentle, but if you’re going from Lake Placid to Saranac Lake, be prepared for a 1½-mile downhill run that’s considered one of the biggest cross-country thrills in the Adirondacks (requiring intermediate skills).

It took the vision of Goodwin and his friends to realize that the disparate tracts of state land, ski centers and golf courses offered a unique opportunity to create the first (and so far only) long-distance ski trail in the Adirondacks. “It started with a lot of people meeting in living rooms and saying, ‘Hey, there’s a lot of terrain out there. If we could only find a way to tie it together,’” recalls Goodwin.

After negotiating easements with landowners and much physical labor, the Adirondack Ski Touring Council opened the trail in 1988. The founders named it after Herman “Jackrabbit” Johannsen, the legendary Norwegian who helped popularize ski touring in the Adirondacks in the early 20th century. Johannsen had died in Norway the year before at age 111. He skied almost until the time of his death.

I meet Goodwin at the Rock and River on a warm day in late March. From the lodge, we enter the Sentinel Range Wilderness on skis, following an old road that draws us deeper and deeper into the quiet of the forest. We enjoy an unfolding view of the dramatic cliffs on the north side of Pitchoff Mountain. Just beyond a height of land, we pass frozen waterfalls that are popular with ice climbers. Often, the thwack of tools striking the ice can be heard long before you reach this scenic spot. We next descend a slight but steady grade that ends at Route 73.

After crossing the highway, we wind our way through a dense patch of dark evergreens and past a series of snowy beaver ponds before popping out of the woods at Cascade Ski Touring Center, where we stop for lunch. You can bring your own food or buy a meal at the lodge. Cascade is one of three commercial centers linked to the Jackrabbit. The others are at the Lake Placid Resort and Whiteface Club. Anyone skiing the whole Jackrabbit can purchase a day pass for $12 that covers all three (and the state-run trails at Mount Van Hoevenberg). The other stretches of the Jackrabbit can be skied for free.

Leaving the lodge, we continue on Cascade’s groomed trails for more than a mile before recrossing Route 73 to enter the Craig Wood Golf Course and then the Lake Placid Resort, where a row of boarded-up, unfinished condos stands as proof that the Adirondacks was not immune to the kind of half-baked business schemes that swept much of the nation during the 1980s and 1990s.

It’s afternoon when we reach Lake Placid village. The leaden sky that looked ominous in the morning has lifted. Walking past Mirror Lake and along Main Street, skis slung over my shoulder, I feel like I’m on a springtime stroll, albeit with tired muscles. We pick up the trail again behind the Holiday Inn. This stretch, Goodwin tells me, seems to get more use in the summer. It occurs to me then that we haven’t seen any other skiers all day. Granted, it’s the middle of the week, but this has been one of the heaviest snow years in a long time. And this is a warm, pleasant day.

There are a lot of reasons why the Jackrabbit hasn’t become as celebrated as other long-distance ski trails, such as the 10th Mountain Division Trail between Aspen and Vail in Colorado or the hut-to-hut routes in Norway. Like the rest of the Northeast, the Lake Placid region has suffered from skimpy snowfalls over the past two decades—a phenomenon that has hurt the sport of ski touring in general. And the Jackrabbit does require several road crossings, which Goodwin admits breaks the rhythm of the trip.

Changing demographics probably also play a role. These days, aging baby boomers prefer to go on day hikes rather than on overnight backpacking trips. Likewise, they may not be willing to ski 24 miles, even if the trip is split in two. Goodwin notes that even the 10th Mountain Division Trail has seen this change, as more and more people are skiing to just one or two huts instead of completing the entire route.

As an aging baby boomer myself, I can empathize with those who have lost a bit of their youthful vigor. I skied the 10th Mountain Trail years ago and have done overnight ski trips with the tent, stove and everything else on my back. While I treasure those experiences, I have to admit that ending the first day on the Jackrabbit with a shower and Howard Johnson’s fried clams, topped off by a couple of beers in town, isn’t such a bad way to go either. To my mind, the Jackrabbit offers the best of both worlds: long-distance touring and comfort.

Things would only get better. I awake to find that 22 inches of snow have fallen overnight. My initial ecstasy is tempered a bit when Goodwin, who is to accompany me on the second day as well, telephones my hotel room to say he’ll be late because of the roads. But that’s OK; it gives me time to warm my skis, which had spent the night atop my car and still have a solid layer of well-congealed klister.

When Goodwin arrives with his son Robbie, an aspiring Nordic racer, we pick up the Jackrabbit literally from the parking lot of the Howard Johnson’s. The trail twists and turns along the Lake Placid Outlet and then reaches the Whiteface Club golf course. We run into a couple of snowshoers who are smiling in astonishment at the late-season storm. With the snow still coming down hard, the rolling hummocks of the golf course take on the appearance of a high alpine environment.

The storm has forced us to change our plans, however. Because of the late start and continuing snowfall, I decide not to continue all the way to Saranac Lake. Instead, I’ll turn around at a lean-to in the McKenzie Mountain Wilderness and go back to my car in Lake Placid. The lean-to sits a little below the pass between McKenzie and Haystack (not the High Peak)—where the 1½-mile downhill run begins. From the Whiteface Inn Road, it’s a climb of more than a mile to the lean-to. The Goodwins, who have broken trail most of the day, turn around about halfway there. Robbie has to go to ski practice!

For the first time in two days, I am on my own. There’s always something special about hiking or skiing alone in the wilderness, and the snowflakes dancing among the trees add to the mystique. Even at my leisurely pace, the lean-to comes up entirely too soon. Now I’m tempted to keep going to Saranac Lake, but Goodwin and I have arranged to meet later. So I put on another layer of clothes, spread my wet hat and gloves on the floor and sit down for lunch. Leafing through the lean-to’s log book, I find an entry from July 20 that simply states, “Too many bugs.”

That certainly isn’t a problem today. With an Adirondack lean-to entirely to myself in a dreamscape of wintry tranquility and the anticipation of a downhill powder run before me, I have no complaints at all.

Leave a Reply