Exploring a venerable forest on Peavine Swamp Ski Trail.

By Tom Woodman

On the Peavine Swamp trail system in the northwestern Adirondacks near Cranberry Lake I found a tranquil route through open forest, culminating on a knoll overlooking the Oswegatchie River. Removed from the more challenging terrain of the High Peaks backcountry, the trails allow the skier to settle into a soothing rhythm of kick and glide over level ground and rolling ridges. The occasional gully or steeper pitch is enough to rate the trail’s difficulty moderate or intermediate—but in a low-key way.

It’s a good trip for looking around and appreciating the forest, and on a clear day in early January, I was accompanied by two skiers who were well qualified to be guides through these woods: Jamie Savage, professor at the Ranger School in Wanakena, and John Wood, senior forester for the state Department of Environmental Conservation. Jamie uses these lands as an outdoor classroom for his students. And John, working with Jamie and other partners in the area, has been developing plans for increasing hiking and skiing routes near Cranberry Lake.

We had hustled to arrange this trip because of a forecasted thaw, and we hit the weather perfectly. When I arrived at the Ranger School at midmorning, the temperature was in the high twenties and the sky was cloudless. The temperature hovered around freezing for the day, and a fleece jacket over a turtleneck kept me in the Goldilocks zone, not too hot and not too cold, throughout the trip.

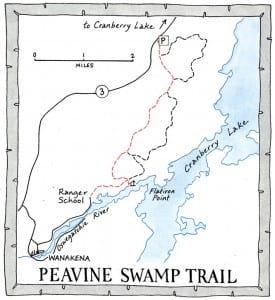

We planned a through route, skiing the main trunk trail of the Peavine Swamp system to the river, then continuing over a trail that leads upriver to the Ranger School for a total excursion of 5.9 miles. So we left my car at the school (the public is allowed to park there, but not overnight) and drove the seven miles to the trailhead where John was waiting for us.

It turned out that John was on the tail end of a nasty cold and had to work at drawing enough oxygen into his lungs as we skied. But fresh air has therapeutic properties.

“There’s nothing better than a day in the field,” he said, voicing the view of every forester who spends more time than they’d like doing paperwork in the office.

While the large Five Ponds Wilderness to the south of Cranberry Lake harbors some of the oldest forest in the Park, Jamie explained that the lands to the north of the lake, where we were, have been logged in the past, but not recently. The last time there was much cutting was following the great blowdown of 1950, when the state allowed loggers into the Forest Preserve to salvage timber from trees toppled by the winds.

The trail runs through the Cranberry Lake Wild Forest, and as it nears the river it reveals older growth. Jamie described it as an “over-mature” forest, meaning some of the oldest and largest trees have begun to die and fall, opening gaps that invite new growth—berry brambles, then cherries and yellow birch.

From the trailhead we skied 3.9 miles to the Oswegatchie Flow lean-to on the riverbank. From there, we backtracked a half-mile to a junction where we took the trail running 0.9 miles west to the campus of the Ranger School. The trail layout also includes three loops, branching off the main trunk trail, so skiers have the chance to customize their trip in a number of ways. The first loop begins 0.3 miles from the trailhead, heading to the east and curling 3.1 miles back to the trunk trail, 0.5 miles farther up. The second loop, also heading off to the east, diverges from the trunk trail at 1.4 miles from the trailhead and covers 2.1 miles before rejoining the main route 3.2 miles up the trunk trail. The third loop circles at the end of the trunk trail and includes the stretch that runs to the lean-to. (Tony Goodwin’s guidebook, Ski and Snowshoe Trails in the Adirondacks, calls the first two loops Balanced Rock Loop and Christmas Tree Loop respectively, but the state Department of Environmental Conservation signs use the numbers.)

As we pushed off from the trailhead we found ourselves on a snowmobile track. This was probably evidence of illegal use, since this isn’t a designated snowmobile trail. The snow in the woods was about two feet deep. Even after the snowmobile track ended where the machine turned around, the trail had been broken by skiers with about two or three inches of fresh snow on top of their tracks so we didn’t have the work of pushing through the deep powder.

We glided through a hardwood forest, a mix of maples, birch, beech, and black cherry. Red spruce are scattered among the deciduous trees. The second half of the trail is in an area DEC says has never been significantly harvested. Large specimens of yellow birch, red maple, and sugar maple are the granddaddies here, some reaching four feet in diameter. These individuals have grown here several hundred years, Jamie said.

The terrain is mostly level for the first 0.8 miles, with a gully every now and then to test our herringbone skills. Pushing out of these gullies could be tricky with the snow. Our poles plunged deep before finding solid purchase. Though the trail passes close to the east edge of the Peavine Swamp, it’s not visible through the forest.

We began to climb steadily after passing the junction where the first loop rejoins our trunk trail. The land begins to fold into rounded knobs and ridges here. We continued climbing in gradual-to-moderate pitches, passing the junction where the second loop leaves the trunk trail and then dropping moderately before ascending over one last ridge and descending to the river. On one tricky little descent where a side hill creates a double fall line, two out of the three of us left sitzmarks. Courtesy prevents me from saying who they were.

As we climbed to the final ridge we saw a shallow trough in the snow describing a sinuous track down the slope, long and graceful curves over the trail: an otter slide. We could see the otter’s tracks where it reached its angle of repose and walked off into the trees. How does the otter steer? And why make these swooping turns instead of sliding straight down the trail? Because it’s fun? That’s my bet.

All along the trail we saw deep tracks where deer had bounded and struggled, expending who knows how much energy as they searched for food. Those signs didn’t send the same message of delight that the otter slide did.

Descending the last ridge, the trunk trail divides to form the final loop. We stayed on the right fork and reached the river and lean-to in a half mile, passing the junction with the trail that would lead us back to the Ranger School. It took us about three hours of easy-going skiing with frequent stops to reach the river. The lean-to is sited on a knoll with 180-degree views of the Flow through the trees. It’s a well-appointed camping spot, with a dock, and even some modest furnishings in the lean-to, including a small table and a handmade broom hanging on the wall.

The Flow was covered in ice and snow, but it wasn’t clear how solid the surface was. We could see some sort of tracks in the snow a couple hundred feet from shore, but we decided not to try our luck and stayed on terra firm.

After lunch and some photos we skied back to the junction with the trail to the school. This stays on level ground paralleling the river for a mile to where the Ranger School sits on the shore. As we neared our destination we began to pass small outbuildings before coming into view of the grand main building. With school on break, the campus sat quietly above the river, a way station between the settlement of Wanakena and the forest extending all around—a portal to the woodlands. ■

Leave a Reply